The term “mental toughness” has become a popular buzzword in strength, conditioning, and fitness circles over the last several years, particularly when it comes to conditioning.

People are even paying good money to run themselves through brutal military style obstacle courses and endurance races – all in the name of proving and developing their mental toughness.

Of course this is really nothing new; coaches, trainers and the military have been running people into the ground for years in the name of developing mental toughness.

The difference now, however, is that people used to do everything they could to avoid this type of training and now people are willing to wait in line and pay their hard-earned money for it.

One could easily argue that the entire culture of CrossFit was built on the concept of mental toughness and proving how “tough” you were by how far you could push yourself in the gym.

In essence, being mentally tough has become a badge of honor and something people are willing to go to great lengths to try to improve.

Despite the growing popularity in mental toughness-type training and events, there’s been almost no discussion about what mental toughness really is, or what the best ways to develop it actually are…until now, that is.

In this article, I’m not only going to tell you the truth about what mental toughness actually is, I’m going to share with you why the way most people approach mental toughness training is complete nonsense that almost always does more harm than good.

Whether you’re a coach, trainer, athlete, or just workout for health and fitness, what I’m about to discuss will help you get more out of your hard work…

What is mental toughness, really?

To truly understand mental toughness, there are two fundamentals that have to be discussed.

The first of these is that mental toughness is nothing more than a function of your brain chemistry. Once you look at it from this perspective, it’s clear that mental toughness isn’t some vague concept – it’s actually just another function of our biology and the way we’re hardwired for survival.

Even more, the science of how the brain works is something that can be studied, and of course has been studied, for decades. In other words, there’s real science that can explain what mental toughness is and how it works.

The second fundamental is really just an extension of the first: mental toughness is the end result of your decisions, both conscious and subconscious.

After all, nobody is holding a gun to your head while you’re training or competing, forcing you to keep going. Only you can make the decision to keep working even as physical and mental exhaustion set in.

Because there are powerful, subconscious factors at work that you have little control over, however, there’s a lot more to mental toughness than just choosing to be mentally tough.

Taken together, these two fundamentals mean that if you really want to understand mental toughness, you have to understand how the brain makes decisions in the first place…

The science of decision making

Each and every day we’re faced with literally hundreds of decisions.

Most of them are fairly inconsequential in the long run– whether you feel like eating a sandwich or a salad for lunch, for example– but others can have a major impact on the rest of your life – who to marry, which job to take, where to live, etc.

In order to deal with both the huge number and the wide range of decisions, our brains have developed different processes to handle different types of decisions.

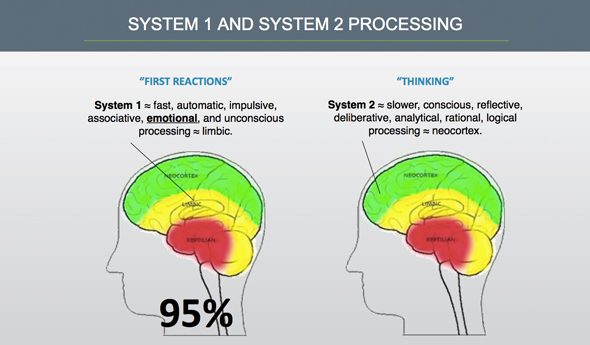

Nobel Prize winning behavioral psychologist Daniel Kahneman uses the terms “System 1” and “System 2” to describe how these different processes work and interact with one another, so we’ll use the same terminology here.

As it turns out, both of these systems play a role in mental toughness.

First, let’s talk about System 1…

How system 1 works to save you time and valuable energy

From an evolutionary perspective, System 1 is absolutely essential to survival and it’s what drives our subconscious-level decisions. These turn out to be most of the decisions we make on a daily basis.

Think of an animal in the wild that encounters another animal:

Almost instantly, the animal must decide whether the other animal is a friend or a predator. The wrong decision here can mean death, so the speed at which the decision can be made is absolutely crucial.

In order to make decisions quickly, System 1 works through heuristic techniques, which simply means that it sacrifices accuracy in the name of speed.

Let’s say you see a pile of change on the coins sitting on the table. Would your first instinct be to take the time to count and add up each and every coin to figure out how much money was there, or would you look at the pile and use intuition to estimate the amount instead?

Unless you need an exact amount of change for something in particular, chances are that you’ll just take a quick glance and come up with a ballpark estimate based on your instincts.

For many decisions, particularly ones that need to be made quickly, our brain simply comes up with a solution quickly that is close enough to the right answer.

In other words, instincts are the result of an actual biological mechanism which explains where they come from and why you have them.

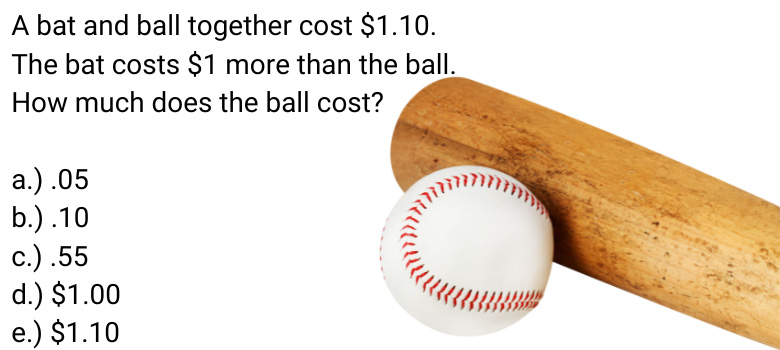

To see how this works for yourself, consider the following math problem from Kahneman’s research:

If you answered 10 cents that’s an example of System 1 at work. Intuitively it seems like this is the right answer…but it’s not. The answer is actually 5 cents.

(You can copy and paste the question in your search engine if you want to know why)

If you got it wrong, don’t worry, you’re not alone. Kahneman showed in his research that more than 50% of students at the prestigious schools of Harvard, MIT and Princeton failed to get the answer right when it was posed as a question during a class. At other colleges, it was even higher, up to over 80%.

Why do so many intelligent people fail to get this simple math problem wrong?

The answer is that this is System 1 at work – it analyzes options and situations very quickly and then makes a decision.

It’s up to System 2 to double check and to see if this answer is actually correct, but we’ll talk more about that later.

So what does this have to do with training and mental toughness?

To get to the answer, we have to consider exactly how System 1 makes decisions in the first place and this is where things get really interesting…

The basis of how System 1 makes decisions is centered on predicted benefits weighed against predicted risks associated with different choices.

What this means is that when making fast, subconscious-level decisions, the brain evaluates options by predicting which choice will lead to the biggest benefit and comparing this against potential risks.

The underlying details of how this works relies on the dopamine system, what many people refer to as the “pleasure” or “reward” system.

Contrary to what most people think, however, dopamine is not really about the reward or the “pleasure” per se, but instead it’s about the prediction of the reward, or potential benefit, of a decision.

In the brain, you have billions upon billions of neurons that are sensitive to dopamine. When your brain considers two options –let’s say it’s what to eat for lunch, for example– each of the options will cause different neurons to fire.

You have a group of neurons in the brain that fire when you think about eating an apple, a group of neurons that fire when you think about eating a piece of cake, a group that fires when you think about eating a salad, etc.

In order to evaluate which is the best choice, the brain essentially measures the firing rate, which is the result of the dopamine signal, of each different option.

If you prefer an apple to an orange, for example, then when you’re considering which to eat, the reason you end up eating the apple is because your “apple neurons” are firing at a higher rate than your “orange neurons.”

The brain interprets this as a signal that you’re more likely to experience greater benefit eating the apple than the orange and thus the decision to eat the apple is made.

A great deal of research in from the field of Neuroeconomics shows us that many decisions like this are entirely subconscious.

You may think you deliberately chose the apple out of your own free will, but in reality the decision was made by your brain without your conscious input or control.

Keep in mind that while there is a way to override this system (and we’ll about that soon), most people wouldn’t spend an hour contemplating whether or not they want to eat an apple or an orange; they’d simply go with what sounds good at the time.

This is System 1 at work.

Perhaps the most interesting thing about this process of valuation is how it gives you the ability to learn from your decisions.

Let’s say that you pick one food over another to eat for dinner at a local restaurant, but that food ends up giving you food poisoning and you get sick.

The next time you consider eating that food, less dopamine is produced and the neurons sensitive to that food don’t fire at the same rate. Suddenly, based on your bad experience, the brain values that food much less than it did previously and thus it’s more likely to choose a different food.

Again, remember that dopamine is not about the reward, but rather about the prediction of the reward.

After a food makes you sick, less dopamine gets produced when thinking about that food the next time because the brain has learned from the bad experience and it starts to predict a lower level of reward and a higher level of risk associated with that food.

The same process of valuation and learning happens with all decisions that System 1 makes and that includes decisions made about training and how hard to work as well.

The greater the predicted benefit of doing the work versus not doing the work, the harder the brain will push the body.

tweet thisGoing back to the idea that how hard you push yourself is nothing more than a decision, it should now be clear that this all comes down to how much the brain values the work that’s being done.

The greater the predicted benefit of doing the work versus not doing the work, the harder the brain will push the body.

If you knew you’d be given a million dollars to run a marathon with just four weeks of training, chances are that you’d train a whole lot harder than if you were told you’d be given ten dollars to do it.

In fact, most people probably wouldn’t even bother trying for a ten dollar reward, but almost everyone would give it a shot for a million dollars.

What this means is that what most people perceive as “toughness” is really nothing more than the end result of a person’s brain placing a high value on the work that it’s doing.

If the brain predicts a big reward, it will work and work and work and push through physical fatigue and pain.

If it doesn’t, then it will make the decision that it’s simply not worth the exertion and it’ll slow down and/or stop altogether as soon as fatigue starts to set in.

What this all tells us is that much of what we consider to be examples of mental toughness are really just a reflection of how the person’s brain values the work that it’s being asked to do.\

There is nothing superhuman about people that are mentally tough and willing to push through fatigue and pain, it’s just that their brains are hardwired to value the work they are doing more than someone that slows down or quits earlier.

System 2 and the science of self-restraint

Now that we’ve looked at how System 1 makes subconscious level decisions, we can talk more about System 2.

Unlike System 1, the role of System 2 is much more about higher-level thought processes and complex decisions.

After all, there are plenty of decisions that need to be based off of more than just instincts or feelings; this is where System 2 comes in.

Decisions influenced and made by System 2 actually come from a different regions in the brain, and one of the most recently evolved, called the Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex (DLPFC).

Decisions influenced and made by System 2 actually come from a different regions in the brain, and one of the most recently evolved, called the Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex (DLPFC).

This area of the brain handles complex mental activity, working memory, planning and organization, abstract thinking, etc.

System 2 is at work when you’re working on a mathematical proof, reading a complex article, deciding which colleges to apply to, planning what you’re going to do next week, etc.

The evolution of this system is largely what allows us to live in complex societies with many layers of social interactions and behaviors.

The flip side to System 2, however, is that it’s relatively slow by comparison to System 1 and it requires a lot more energy and is susceptible to fatigue.

The more you use System 2, the more difficult it becomes to continue using it. The more fatigued you are, the more likely you are to just fallback on System 1 for your decision making.

This is why your brain feels fried by the end of a taking a long test, or why it’s much harder to concentrate when you’ve had very little sleep, etc.

Activation of System 2 is something we control consciously, but we tend to not use it unless we have to because it requires both a lot of effort and energy to do so.

This is why over 50% of the people at the most elite colleges got the math problem wrong. It’s not that they couldn’t solve the problem, it’s that to do so would require the activation of System 2. Unless the question is on an actual graded test, System 2 activation takes more effort than it’s worth.

In this way, System 2 is a limited resource and subject to fatigue like anything else that requires additional energy.

Research has even linked the ability of System 2 to function to levels of blood glucose. This makes sense, since the brain relies on glucose to produce energy; as blood glucose levels start to decrease, the brain is unable to exert the same level of mental effort.

Relating this back to mental toughness, System 2 has the ability to override the decisions of System 1 to slow down or stop.

This is our conscious-level control over how hard we work. Even as System 1 is saying the work is too hard and not worth the effort, System 2 can take over and consider your long-term goals, aspirations and even fears and tell the body to continue working despite the challenge.

In this fashion, System 2 is our ability to exercise self-restraint.

When we’re exhausted and everything is telling us to quit working so hard at the end of a training session or competition, we activate System 2 to restrain ourselves from slowing down.

Research has even shown how this relates to dieting: the reason some people are able to resist tempting foods while others can’t comes down to a person’s ability to activate System 2 to exercise self-restraint.

Taken together, the roles and actions of both System 1 and System 2 are what define and govern our ability to be mentally tough and persistent even in the face of high levels of physical fatigue.

The way our brain values the work it’s doing, along with our ability to activate System 2 and exercise self-control even as System 1 starts to slow us down, is what will ultimately determines whether we’re able to push ourselves to the edge of our physical limits or if we slow down long before we get there.

How to train mental toughness the right way

Now that we’ve discussed how the brain makes decisions and how those decisions are ultimately reflected in how hard you work and how long you persevere, it’s time to talk about how to apply an understanding of decision-making to training mental toughness the right way…

Rule #1: Always focus on reinforce the value of conditioning work rather than only the effort

The thing that should be the most immediately obvious is that if you’re a coach, simply yelling at someone to work hard, or putting them in situations where their hard work is viewed as punishment, is a major mistake.

Even though yelling, or using the authority of a coach or trainer in some other way, may get someone to work harder than they might on their own, the problem with this approach is that it completely devalues the work itself.

And if you’re just training yourself, using conditioning work and running yourself into high level of fatigue where the only goal is building “toughness” isn’t the right approach.

As we just discussed, the brain makes decisions largely based on the benefits it predicts from different choices.

This means it’s all about value; how much does the brain value the work that it’s doing?

If someone is only working hard because they are being told to, because they think it’ll magically make them tougher, or worse, because it’s a form of punishment, the brain is going to place very little value on the work itself and it’s going to make the decision to stop working much sooner.

This is true for decisions made by both System 1 and System 2.

System 1 will see far less of a rise in dopamine because there’s less anticipated benefit associated with the devalued work.

System 2 will also have no reason to weigh in and override the decisions of System 1 to slow down, because again, there is little value associated with the work itself.

This means that the most crucial element to correctly training mental toughness is to always ensure that the person doing the working clearly understands the value of intensive training.

Instead of just focusing on telling someone to go harder or faster, a coach or trainer should emphasize why they should go harder or faster.

How is the person doing the work going to benefit from their efforts? That is the key question that must be understood if his/her brain is going to choose to continue doing the work over choosing to slow down or stop as fatigue sets in.

Again, this is why using mental toughness-type training as a form of punishment makes absolutely no sense and is a terrible approach – it’s literally teaching the person’s brain that the hard work being done has no real value.

This is a surefire way to get very little out of training and. even worse, it builds terrible motor programs as I discussed in a previous article on Movement Conditioning.

Anyone that’s training needs to always understand how the work they are doing is going to directly benefit them, both in the short-term and long-term.

Focusing on how the work that’s being put in is going to help them reach their goals is the key.

If you’re a coach, use verbal cues that emphasize this instead of just saying the standard fluff like, “Come on, keep going, you can do it!”

Such phrases do very little to convey the real benefit of the work or how it’s going to help them make progress towards their goals.

Rule #2: Focus on measuring and tracking progress towards your goals

A big part of people understating the value of the work they’re doing comes back to whether or not they’re seeing any real progress from their effort.

Unfortunately, most people aren’t tracking anything when it comes to conditioning, and people generally have no real idea of whether they’re improving and by how much.

This is why using metrics to track progress is absolutely crucial: it provides feedback that shows the brain there is a direct benefit to working hard.

One of the best and most effective metric to use for this purpose is Heart Rate Variability (HRV). That’s a big reason why I created my own app that uses HRV, Morpheus

If you’re not sure what HRV is how to use it, click here to learn more

Not only does HRV provide the best overall gauge and long-term tracking of aerobic fitness and general conditioning, but research has even shown that HRV levels correlate extremely well with the ability to activate System 2.

People that show a strong ability to exercise greater self-restraint also show higher HRV on average than people that lack this ability.

This makes HRV an extremely powerful tool to develop mental toughness.

Seeing your average HRV increase over time is a way of objectively seeing the rewards of your conditioning work.

The reinforces why you’re doing it and keeps the dopamine response driving you to continue doing more of it.

To learn some other ways aside from HRV to measure and track your conditioning progress click here

Or, if you’re looking for a conditioning program to help you get started, click here to check out Metamorphosis my 8-week program designed to get you in the best shape of your life.

Rule #3: Train mental toughness separately

Because the ability to activate System 2 is limited and fatigues with lower the levels of blood glucose, it makes little sense to only incorporate mental toughness training at the very end of a long training session, as is so often done.

By this point, you’ve already exerted a great deal of both physical and mental energy, and your ability to truly exercise the highest levels of self-control and keep going are already significantly diminished.

It’s like trying to hammer a muscle group at the end of a workout after you’ve already worked it to death for the last hour.

That doesn’t mean you should never push yourself at the end of your workout or work on your mental performance when you’re tired. But it does mean this shouldn’t be the only time you do it.

Instead, if you’re going to develop mental toughness within a training program and this areas is a priority for you, dedicate an entire training session to it where the sole purpose is to practice this ability.

Start when your fresh and able to active System 2 to keep them going instead of only training mental toughness when they are already exhausted to begin with.

A side note to this is that if you are going to do mentally tiring things at the end of a training session, it’s important to keep blood glucose levels up by taking in a small amount of liquid carbs throughout the session.

This will help ensure that the brain has more of the energy it needs to solve complex problems and consider the long-term benefits of what it’s doing.

In short, it’s always important to build your workouts around your priorities.

If building the mental side of fitness is one of them, then it shouldn’t just be something you only do during the last 5-10 minutes of your workout as part of a “finisher”.

It should be built into your workout from start to finish.

You don’t have to be make yourself tired to train mental toughness, focus, concentration, etc.,

To see what I mean, here’s a great article by a friend of mine named Brain Cain that’s one of the top mental performance coaches in the business.

How to learn more

The idea of using difficult forms of physical training to try to develop mental toughness has been around for decades, or perhaps even longer.

If you’re a coach or trainer, hopefully you now understand that going about this the right way involves much more than just running someone into the ground while yelling motivational phrases about how they can do it.

The body and the brain work the way they do for distinct biological reasons. The better you understand what’s driving the decision-making process, the more effectively you’ll be able to tap into these processes to develop mental toughness the right way.

To learn all the details and the most effective ways to specifically coach to improve mental toughness, make sure to register for the BioForce Conditioning Certification (CCC), the next time it opens.

Another article exploring brain and stamina.

Terms are a little different but seem to be saying best performers fire up System 2 more before exertion but less during.

http://zhealtheducation.com/episode-79-stand-your-way-to-greater-stamina/

http://discovermagazine.com/2014/oct/12-feats-of-will