Football season is in full swing. Teams across the country are practicing during the week and playing games on weekends. Many fans wonder when these athletes have time to workout or train outside of practices. Depending on which player or coach you ask, you will get different answers.

In general, the answers you’ll find to this question will look something like this:

“We work out on our own, not with the team” – Confused Player

“We still train the same as the off-season. You can’t stay in the same place, you can only get better or get worse!” – Hardcore Coach

“Our general training program still exists but it complements our practices and game schedule” – Wise Physical Preparation Coach

Fortunately for you, I’m going to talk about the practices of a Wise Physical Preparation Coach who knows a thing or two about in-season training. That individual is Buddy “Coach X” Morris, the Head Physical Preparation Coach of the Arizona Cardinals.

This article will outline the general principles Buddy adheres to when designing and implementing an in-season program.

Maintain and Restore

To start, the main objective of a physical preparation coach and the training they implement for their athletes during the season is to get their athletes ready to perform to the best of their ability on game day. Let’s not lose sight of that fact.

There is no other objective that is more important than this during the season. Physical preparation should play a support role, not interfere or compete for reserves and energy during the season.

Knowing this, workouts are designed to do one of the following: maintain (or retain) a biomotor, biodynamic, or bioenergetic quality or restore the fitness, preparedness, and readiness of an athlete acutely.

Physical preparation should play a support role, not interfere or compete for reserves and energy during the season.

tweet thisIf you’re familiar with Vladimir Issurin’s work, you will recognize this taxonomy of workout goals:

- Development

- Maintenance

- Restoration

Thus, we do not aim to develop any ability or quality during the season, only to maintain or restore it.

The next question that arises is, “How do you know where the line is drawn between developing and maintaining, or maintaining and restoring?”

Like all things in physical preparation, there is not a fine, magical line that separates one entity from another; there is a fuzzy, blurred line which bleeds into each category.

As far as in-season training goes, the coach or athlete (who trains him/herself) must make the best decision possible to ensure the workouts target maintenance and restoration rather than tax the individual by becoming a developing workout.

Let’s pause for a second to clear something up. During a competitive or in-season period, what abilities are actually being developed? Hopefully, you realize the answer to this immediately: sport-specific abilities are being developed.

Every time a team hits the practice or game field and performs exercises, drills, and games that are specific to the competitive exercise/game in a bio-motor, bio-dynamic, or bio-energetic sense, they are developing all of those qualities and abilities needed to perform at the highest possible level.

Now, you might ask, “How do you know these abilities/qualities are being developed?” Simple. The integration of volume and intensity is great enough that the work performed causes a beneficial adaptation (i.e. higher force output from hip extensors, denser mitochondria in local musculature, faster/more efficient biochemical reactions, etc.) for the athlete.

Just as with developing workouts, the best way to gauge maintenance and restoration workouts is to track and calculate the integration of volume and intensity. For example, lets take a look at what would be a developing, maintenance, and restoration workout for upper-body strength training.

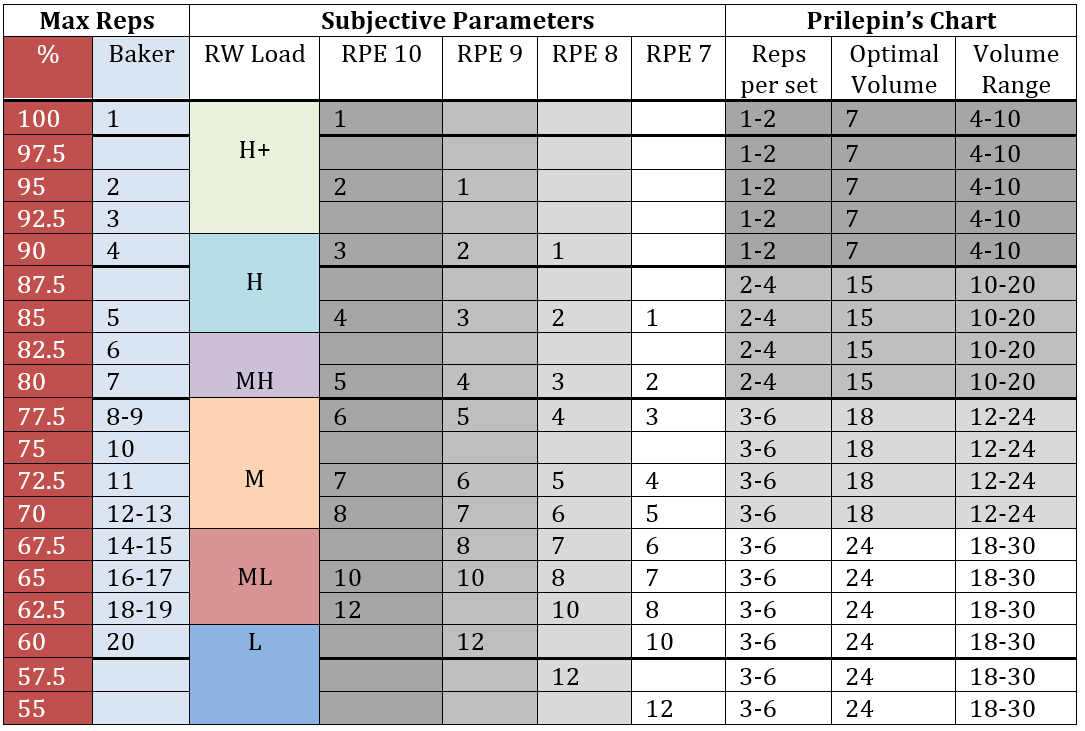

Most of you are probably familiar with Prilepin’s chart. If you are not, here is a picture of the chart below:

Prilepin’s Chart is shown in the far right of the table. Let’s focus on the bottom right section of the table where the reps per set, optimal volume, and volume range correspond to 55-67.5% of a one-rep max.

For the first example, let’s design a development workout:

We choose an exercise intensity of 60%. Using Prilepin’s chart, we see that corresponds to 3-6 reps per set, an optimal volume of 24 and a volume range of 18-30. Since the goal is development, the volume needs to be on the higher range.

When we’re done, we come up with a workout that looks like this:

Developmental workout:

Bench Press (or any press) @ 60% for 6 sets of 5 reps

In order to just maintain this quality, there are a two options: reduce the intensity or reduce the volume. Since the intensity is already relatively low, we should reduce the volume.

Maintenance workout:

Bench Press (or any press) @ 60% for 3 sets of 5 reps

We make even greater changes to the workout when the goal is restoration. In most cases, a combination of the usual exercise and means associated with restoration and recovery are utilized. For example:

Restoration workout:

Floor Press (reduced ROM) @ 55% for 1 set of 5 reps

Foam Roller complex 10-20 passes on chest

Pectoral Stretch 2 x 30 seconds

This should come off as being simple and straight-to-the-point. Again, this is NOT an exact science. Many factors come into play, such as preparedness, readiness, training experience, injury status, etc. Use your best judgment when addressing all of these variables.

What’s Next

In the next article of this series I will go more in-depth on designing maintenance and restoration workouts along with how to set up the entire training week around practices and games.

To learn the actual physical preparation and speed training methods Buddy Morris uses with the Arizona Cardinals, check out the course we made together on the BioForce Project: American Football Physical Preparation.

Hello

So 60% of 1rm is developmental in the Bench Press ?

For what explosive strength ? Even at 6 sets of 5 repetitions

it seems that would not do anything but maintain absolute strength.

Brandon

Hi Brandon,

With strength and weight training, each combination of intensity, volume, and density will elicit specific adaptations to bio-motor abilities (like strength, as you spoke of), bioenergetic qualities, and biodynamic parameters.

Specifically to the scenario at hand, explosive, starting, acceleration, and absolute strength will be developed to varying degrees, depending on the individual. Furthermore, a slight amount of hypertrophy will take place with this intensity and volume interplay.

Typically, 6×5 @60% will develop explosive strength, this set-up will on have a small effect on absolute strength, more so the less trained an individual is.

Hope that helps,

Ryan